Razorback pigs or feral hogs, an iconic symbol of the American South, have a history and lineage that is both intriguing and complex. Their origination, evolution into a feral state, and eventual dispersion across the American continent is an engaging narrative often interwoven with the fabric of American society itself.

Their distinct characteristics, ranging from their unique physique, lifespan, to breeding habits, differentiate them from other breeds, making them fascinating subjects to study. Delving deep into the world of razorbacks, this text navigates their journey from foreign shores to America, from cordial historical relationships to burgeoning challenges, and from environmental implications to contemporary management and control efforts.

Origins of the Razorback Pig

Origins of the Razorback Pig

Sometimes called feral hogs or wild hogs, Razorback pigs have a diverse past. Though their official scientific name would suggest they originated in Europe – Sus scrofa is also known as the European Wild Boar – their history goes beyond the boundaries of Europe. The wild boar can be found across Europe, Asia, and North Africa, indicating a broad geographical range in its past. The species shows high flexibility and adaptability traits, which could partially explain their successful migration across continents.

Migration to America: Spanish Explorers and Free-Range Practices

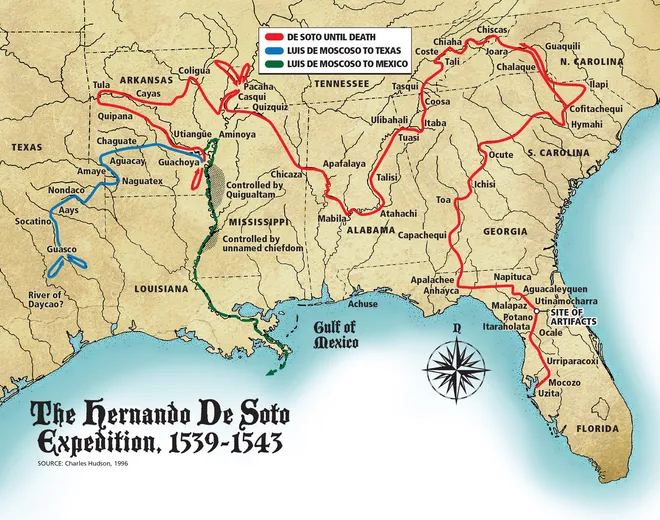

The feral hogs’ history in America begins in the 1500s with the arrival of Spanish explorers. Christopher Columbus had domestic pigs onboard during his second journey in 1493, initiating the species’ introduction to the New World. Similarly, Hernando de Soto, another Spanish explorer, is known to have brought pigs to Florida and, by default, to mainland America around 1539.

Back then, free-range livestock practices were prevalent. Pigs were often let loose to forage in the wild, breeding with the descendants of wild boars brought in earlier by explorers. It’s believed that this unregulated interbreeding resulted in a population of domestic hogs turning feral.

Evolution into the Razorback

Over generations, these feral pigs began to adapt to their wild environments and evolve into the Razorbacks we see today. The term “Razorback” refers to the distinctly sharp-ridged back that some of these hogs developed, akin to a ridge of razor blades. They also show other characteristics that reflect their adaptation to the wild: long, rubbery snouts beneficial for extensive rooting in the ground; tusks for competing with rivals and defending against predators; and agile, muscular bodies capable of running at impressive speeds.

Razorbacks have the ability to thrive in numerous environments including forests, wetlands, grasslands, and agricultural lands. This adaptability has led to them becoming established across much of the southern United States.

The Influence of Environment and Cross-Breeding

The environment played a big role in shaping the characteristics of the Razorback. From the pig’s versatile diet to its hardy nature, these traits are results of adaptations that helped the species survive in the wild, undomesticated environments.

The introduction of Eurasian wild boars in the 20th-century for sport hunting further complicated the story of the Razorback pig. The Eurasian boars, being more aggressive, bred with already existing American feral hogs, including the Razorbacks. This cross-breeding has led to even more variations within the feral hog populations in America.

The story of the Razorback pig is one marked by resilience, adaptability, and survival. Originating from domestic pigs, these creatures evolved into the feral hogs known as Razorbacks in response to changing environments and the influence of cross-breeding. This journey stands as a testament to the species’ versatility and survival prowess.

Characteristics of Razorback Pigs

Characteristics of Razorback Pigs

Razorbacks are distinguished from other hog species by their high, ridged back (hence the name ‘razorback’), long, oval-shaped heads, and thin, wiry physique. They are largely covered in coarse, bristle-like hair, which can range in color from black, brown, or red to white or spotted, depending on the individual pig’s ancestry. Adult razorbacks generally weigh between 100 to 400 pounds, but some males have been known to reach over 500 pounds. They have notably long, sharp tusks that they use for defending themselves and their territories.

In terms of lifespan, razorbacks tend to live between four to five years in the wild, but in captivity, they can survive up to ten years. These pigs are well-equipped for survival, being omnivorous creatures that can eat a wide range of food, from plant material and roots to small animals and carrion. Their excellent sense of smell assists them in foraging for food, and sharp tusks help with both hunting and self-defense.

Breeding Habits & Population Growth

Razorbacks are notoriously prolific breeders, contributing to their rapid population growth in the wild. Women pigs, or sows, can start reproducing as early as six months old and can have two litters a year, each consisting of between four to six piglets. Sows are protective mothers and will aggressively defend their offspring.

This rapid breeding rate, combined with a lack of natural predators and adaptable eating habits, has contributed to a significant increase in the razorback population. Biologists estimate the U.S. has a population of more than five million feral pigs, spread across 35 states, with the highest concentrations in the southern regions.

Photo Credit: UofK Martin-Garrin

The Influence of Razorback Pigs

Razorback pigs, though well-adapted to living in the wild, potentially cause harm to their surrounding ecosystems, leading to their classification as pests. These creatures’ tendency to root and forage can result in soil degradation and disruption of native plant and animal species. Furthermore, they can act as carriers for diseases, putting livestock, wildlife, and on occasion, humans at risk.

However, despite these drawbacks, the tenacity, adaptability, and ruggedness of the razorback pigs commands a certain level of respect. These qualities have facilitated their survival and spread across diverse environments over hundreds of years.

History of Razorback Pigs in America

The Journey of Razorback Pigs to North America

Razorback pigs, also known as feral hogs or boars, are not indigenous to North America. The present-day razorbacks in the Southern United States, in fact, trace their origins back to domestic pigs introduced by early Spanish explorers in the 16th century. Explorer Hernando De Soto is often credited with bringing the first hogs to North America, with many of these pigs either escaping or being abandoned. This stock soon reproduced and spread extensively across the southeastern United States.

Further contributing to the population of feral hogs were English and French settlers, who brought with them their own breeds of domestic pigs. Over time, some of these pigs escaped or were released into the wild. These animals, subsequently breeding with the descendants of the Spanish pigs, have formed the diverse population of feral hogs seen today.

Evolution into the Wild Razorbacks

As these domestic pigs were introduced to the wild environment, they began to evolve and adapt to survive, giving birth to the Razorback Pigs we know today. Razorbacks gained their distinctive hardened, hump-like backs over the generations due to natural selection—the firmer back muscles helped the pigs root more efficiently for food.

Impact on American Society and Economy

Razorbacks played a significant role in the lives of early American settlers—these feral hogs provided a readily available source of food and materials. They could be hunted relatively easily due to their abundance and, with no predators, their population thrived. For many in the South, hunting and eating Razorbacks became a staple part of their culture, which persists to this day.

However, drastic growth in the razorback populations has had economic consequences as well. With an estimated 6 million feral hogs in the U.S today, they are considered an invasive species and are a cause for concern in many regions. Razorbacks are responsible for approximately $1.5 billion in damage annually, mainly due to their feeding habits. They cause severe damage to crops, pastures, and landscapes as they root in the ground searching for food.

Cultural References and Present Day Significance

The Razorback is deeply ingrained in Southern American culture. It has ties to sports, such as the University of Arkansas choosing the Razorback as its mascot due to its embodiment of tenacity and fight.

Despite the problems they cause, razorbacks are a popular game animal, offering both economic and recreational opportunities for hunting. They are known for being challenging to hunt due to their high intelligence, excellent sense of smell, and strong survival instincts, making them a coveted prize for hunters.

To understand the complex history of razorbacks, or feral hogs, in America, we must look back to their introduction by early explorers. Over time, these animals have evolved and adapted to their new environment, becoming a symbol of America’s unique biodiversity and cultural heritage. Their influence extends beyond ecology, impacting America’s economy and cultural history, making them a fascinating species in more ways than one.

Current Status &and Impact of Feral Hogs

The Journey of Razorback (Feral Hog) Pigs to America

It may surprise many to learn that the feral hog, or razorback, is, in fact, not indigenous to the United States. Their roots can be traced back to Europe and Asia where they were initially reared for hunting. In the 1500s, Spanish explorers brought the first of these hogs with them on their expeditions to the United States. Gradually, other varieties of pigs, brought over by European settlers, intermingled with these initial hogs, resulting in a diverse population of feral pigs in the New World.

Over the centuries, numerous attempts at domestication were made; however, the tendency for these pigs to escape pens, coupled with deliberate releases for hunting purposes, saw the feral hog population flourish in the wild. Razorbacks are easy to identify due to their distinctive beard-like mane, angular skull structure, and the prominent ridged back that has earned them their name. Their coloration ranges from black, brown, to white, and they can have a hefty weight, often exceeding 400 pounds.

Current Status of Razorback Pigs

Today, razorback pigs are considered a prolific invasive species in the United States because of their rapid reproduction and adaptability to different environments. They are widely distributed across the country, with significant populations evident in states like Texas, Florida, Louisiana, and other southern parts of the country. Nationwide, the estimated population is thought to be over 5 million, with approximately half residing in Texas.

Impact on Urban and Rural Communities

Feral hogs have a significant impact on both urban and rural communities. They are known to be opportunistic feeders, meaning they can eat almost anything including crops, small livestock, and even the eggs of endangered species. This feeding behavior significantly impacts local agricultural production, costing billions in damages annually. Similarly, in urban settings, feral hogs can pose safety risks due to their aggressive behavior when threatened and their potential to spread diseases.

Ecological Impact of Razorback Pigs

Ecologically, feral hogs can wreak havoc in ecosystems where they are not native. Their feeding and rooting behavior can lead to soil erosion, disrupt native plant communities, and decrease biodiversity. They can also compete with native wildlife for food resources and can even prey upon certain native species.

Management and Control Measures for Feral Hogs

The high adaptability and rapid reproduction of the feral hog have made it a challenging pest to control, requiring a comprehensive and integrated approach. Current management efforts are multifaceted, employing tactics such as hunting (both ground and aerial), trapping and snaring, use of trained dogs, and in some places, fertility control.

Drawing on advancements in technology, methods such as remote-controlled traps and the use of thermal imaging for night hunting are also employed. More extreme methods, such as toxic baits, are also under consideration, although concerns about non-target species and human safety have limited their use.

Conclusion

As the story of the razorback pig in America continues to unfold, the feral hog’s broad geographical distribution, ever-increasing population, and varied impacts on communities and ecosystems remain topics of great interest and concern. These formidable beasts, once tamed farm animals, have become the subject of ecological concern and management challenges.

Yet, their survival instincts, adaptability, and resilience further reveal an intriguing narrative about nature, adaptation, and survival. It is through understanding these complex creatures and their history that we can better manage and cohabit our shared spaces, painting a comprehensive picture of their role within the fabric of American sociocultural and ecological tapestry.